For humans, one way to understand natural numbers is counting.

For computers (cf. logic.typ), the source of representing natural numbers is periodic circuits. The binary in memory can directly represent numbers. For example, for 3 bits:

| binary | decimal |

| 000 | 0 |

| 001 | 1 |

| 010 | 2 |

| 011 | 3 |

| 100 | 4 |

| 101 | 5 |

| 110 | 6 |

| 111 | 7 |

A computer’s arithmetic unit can perform calculations on numbers.

There are also various more complex computer behaviors like “functions that recursively call themselves”, which is also a form of counting.

However, the number of elements in the set of natural numbers is infinite, while bits and computer memory are finite. Human memory is also finite.

Problem of infinite space: Reality cannot construct circuits and memory of infinite space. Even if it could, it would be limited by the finite speed of electric current.

But “potential infinity” can be achieved using potentially infinite time.

Assuming the upper limit of memory is infinite but memory usage per cycle is finite, then a program has infinitely possible inputs, which is also a form of potential infinity.

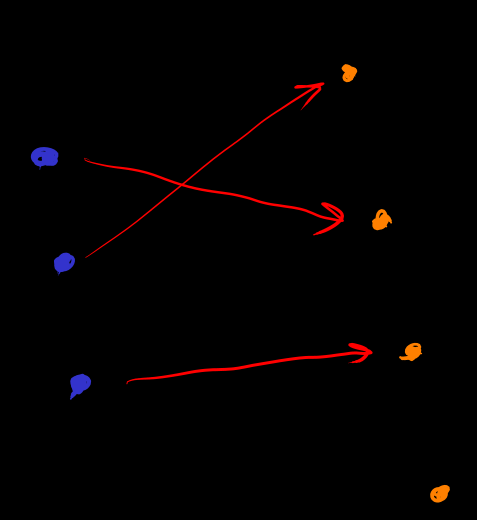

Theoretically, all natural numbers can be counted one by one. However, there are even sets with an uncountable number of elements. They are infinite and cannot be counted. Example

- All subsets of , or (i.e., all functions from to )

- All functions from to itself,

Verifying the correctness of set theory/languages requires a parser, or for mathematical languages, also called a prover.

Motivation for sets/types

-

Modularity and multiplicative decomposition to simplify cognition

Example The subject-verb-object SVO in natural language. Suppose there are 10 nouns and 10 verbs. If we “forgot the SVO rules”, then verifying the grammatical correctness of a three-word sentence would require at most attempts. If we understand and use SVO rules, it would require at most attempts.

-

If the number of elements in a set is infinite, then the set/type will be conceptually finite, making it possible to state within a finite time

Complex mathematical objects are stored in variable names, so humans still need to check the correctness of all complex definitions stored in variable names, which is why code readability is very important

A prover allows humans to reduce from needing to review all steps to reviewing definitions (and checking the compiler’s logical code), skipping a large number of detailed proof steps, and still being able to determine the correctness of the proof result

The human brain compiler can omit and supplement omissions, trading temporary efficiency for error-proneness and forgetfulness

In addition to verifying the correctness of proofs, provers can also have other uses, for example, similar to tools in programming languages, they can have friendly and interactive compiler error messages, and LSP (language server protocol) tools

prover 的例子: acornprover, lean

Let’s not go into details here for now, just a brief overview

[proposition] [theorem] An unproved proposition/theorem is a function from type to ,

theorem p(x: T) {

// ...

}

theorem p(x: T) {

// ...

}

is proven := the prover’s calculation result for always returns true. Can be understood as (usually omitting = true)

forall(x: T) {

p(x) = true

}

forall(x: T) {

p(x) = true

}

Although we have not yet given the construction rules for types

[set] A set of type is essentially a function from type to , . But using a wrapper layer is sometimes convenient

structure Set[K] {

contains: K -> Bool

}

structure Set[K] {

contains: K -> Bool

}

A set of type is represented as

a: Set[K]

a: Set[K]

An element of type belongs to is represented as

a.contains(x)

a.contains(x)

or

x ∈ a

x ∈ a

The empty set empty[T] corresponds to the constant false function. The universe set universe[T] corresponds to the constant true function.

According to the definition of subset in common set theory, it can be written as

Equality can be understood as a binary Boolean function

equal(x: T, y: T) -> Bool

Satisfies transitivity

a = b and b = c implies a = c

- forall, exists (all, exist)

forall(a: T) {

// ...

}

exists(a: T) {

// ...

}

forall(a: T) {

// ...

}

exists(a: T) {

// ...

}

Or written as

- inference (推导)

p implies q

p implies q

Or written as

- equivalent

p = q

p = q

Or

p iff q

p iff q

or

(p implies q) and (q implies p)

(p implies q) and (q implies p)

or written as

The following calculation results can be proven to be equal by exhaustion

Similarly, to represent the case of “infinite elements”, define the De Morgan law for infinite elements

Similar to the redundancy of , set/type construction rules may also have redundancy, or many equivalent definitions

follow various rules for bool in finite cases, define

[commutative-forall-exists]

same for

[distributive-forall-exists]

(Need to assume the existence of function ?)

Natural language examples of derivation

It’s raining

So I won’t go out

This example is similar to a conditional branch

let rain : bool;

let out : bool;

match (rain) {

true => out = false,

false => out = undefined,

};

let rain : bool;

let out : bool;

match (rain) {

true => out = false,

false => out = undefined,

};

Similar to the if block in common programming languages, it automatically skips the execution area when the condition is not met

if (rain = true) {

out = false

}

if (rain = true) {

out = false

}

For mathematical language, that is

- prover reads

- prover reads is true (possibly from definition)

- prover reads is true

- prover assigns the boolean value of to true based on this condition (from memory)

If “void implication” similar to skipping an if block is accepted, then there will be

and find that is

[reverse-inference] Reverse inference. If the result is that I went out, then it must not be the result of rain. If the result of the conditional branch is out = true, this is not the result of rain = true. Since the boolean value of an ideal binary computer must be one or the other, it can only be the result of rain = false. This can be written as a conditional branch

match (out) {

true => rain = false,

false => rain = undefined,

};

match (out) {

true => rain = false,

false => rain = undefined,

};

Mathematically, reverse inference is written as the formula , and defined as equivalent to

[natural-number]

natural number

natural number set is an inductive type

inductive ℕ {

0

suc(ℕ)

}

inductive ℕ {

0

suc(ℕ)

}

Computers cannot handle infinity. To enable computers to represent the set of natural numbers with finite characters and memory, we treat and the function as finite symbols in memory addresses, such that

is equivalent to telling the computer how to continuously using an instruction stream? This also relates to induction.

The cost of finite characters is potentially infinite time, always relying on counting or periodic circuits.

definition

Since “definition language expansion” is long, it is usually abbreviated to “definition” “def”

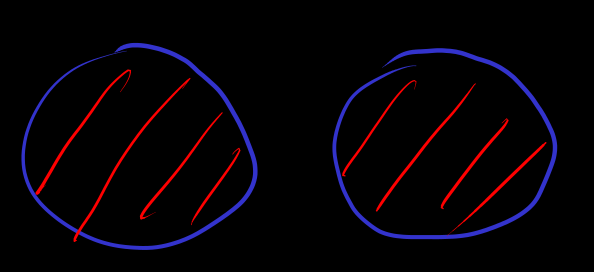

[product]

let be set, then is set

The expression is a product data structure.

Abbreviation . in finite case, number of elements

[sum]

let be set then is a set

also known as tagged union

in finite case, number of element

[function]

let be set. Define function space , the rule for map is

or

denoted by

denoted by . in finite case, number of elements

In a prover, the definition and behavior of a function are: input type + output type + if the same input is checked, the output is specified to be the same

Prop . can correspond to

[subtype]

Adding a proposition to a type and using logic and can yield a “subtype”. It’s similar to a subset, but uses dependent types to add a layer of wrapper.

define(a: Set[K]) -> Type {

structure {

val: K

} constraint {

a.contains(val)

}

}

define(a: Set[K]) -> Type {

structure {

val: K

} constraint {

a.contains(val)

}

}

If a theorem about type is proven, sometimes, it’s easy to see that it holds for certain subtypes. But for a computer, the theorem might need to be rewritten. One way to mitigate this tedium is to use typeclasses to represent structural types and their properties, so that theorems are based on typeclasses, thus increasing reuse and reducing repetition.

function space introduces higher-level infinity

Something counter-intuitive at first glance is that we seem to know all or all , yet we cannot count them cardinal-increase uncountable. But, what exactly does “knowing all “ mean? In fact, trying to consider the problem of “finding an infinite subset of in a general way” will reveal that it’s not simple.

Similarly, although countable can already define some real numbers e.g. , if not using or , only countable constructions cannot obtain all

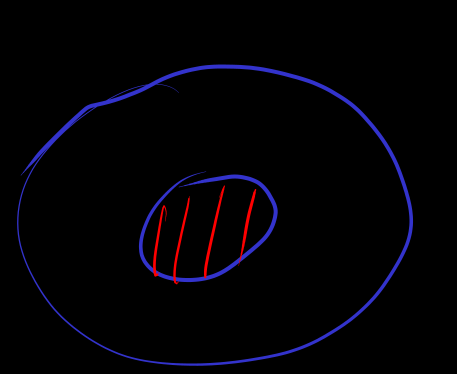

[subset]

Since false, according to vacuous implication,

denoted by . in finite case, number of elements

let

Or if “construct set theory with type theory”, then the definition of equality of sets reduce to the definition of equality of functions

let

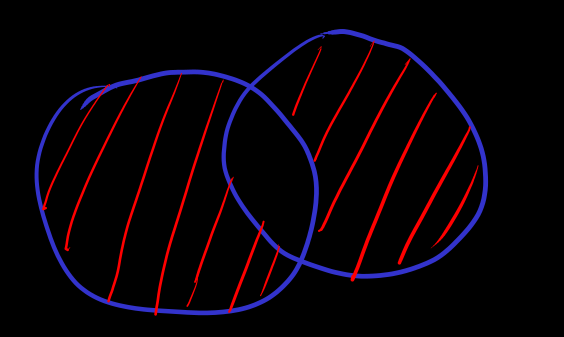

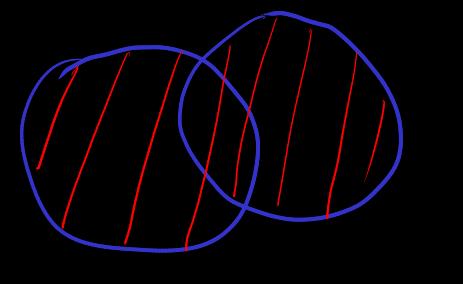

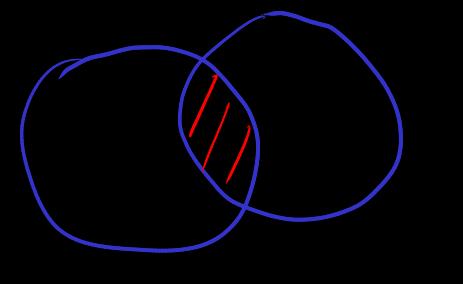

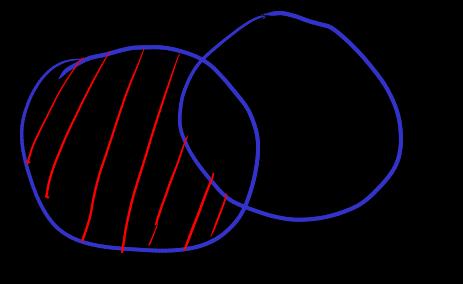

[union]

[intersection]

Note that the elements of union and intersection are restricted to type . In ordinary set theory, if one tries to define the intersection of an empty family of sets, if not restricted to type (or restricted to a certain set), then due to the vacuous argument, the result of the intersection of an empty family of sets is the universal set , and the universal set is not a set, which violates the rules of set theory construction

The intuition that the intersection of an empty family of sets is the universal set: because intersection is decreasing with respect to , thus the intersection continuously increases towards the empty family of sets

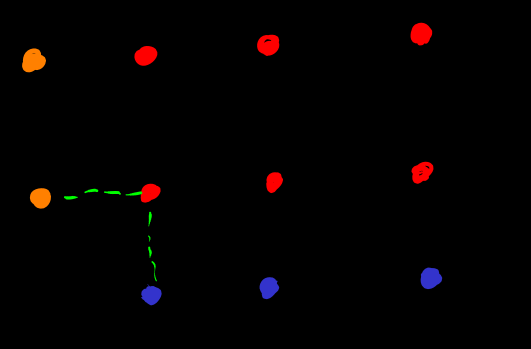

Based on the index mapping , infinite versions of product, sum can be defined

- [product-index]

product component

or

- [sum-index]

sum component

[hierarchy-order-of-set]

The type/set constructed above is called zero (hierarchy) order type/set

or

We can assume

Again using type construction rules, what is obtained is also defined as belonging to

Can also continue

. And so on …

Example

-

typeclass G: Group {mul(g: G, h: G) -> Ginverse(g: G) -> G// property of group}typeclass G: Group {mul(g: G, h: G) -> Ginverse(g: G) -> G// property of group}

looks like the set of natural numbers , so should we assume a new hierarchy ? Then for , continue to use the type construct rule … (will it lead to needing infinite language rules?)

belongs to and belongs to , but these two “belongs to” language rules are different

[universal-type]

The problem of universal-type, or the problem of type of every type

What is easy to overlook here is, what does “type” in “type of every type” refer to? What does the so-called “type” mean?

Assuming the program defines a concept of universal-type, and universal-type can in turn be used to construct “type”, then universal-type refers to itself in the construction rules of “type”, leading to non-terminating languages or programs.

Example [Russell-paradox]

defined using set theory rules

Then try to calculate the boolean of another proposition . Since = true, the prover only needs to calculate the boolean of , then finds not, so it tries to calculate the boolean inside not, but this goes back to calculating the boolean of , entering a circuit deadlock.

Example [self-referential-paradox] Self-referential paradox. “This sentence is false”

this_sentence_is_false : bool = false;

loop {

match (this_sentence_is_false) {

false => this_sentence_is_false = true,

true => this_sentence_is_false = false,

}

}

this_sentence_is_false : bool = false;

loop {

match (this_sentence_is_false) {

false => this_sentence_is_false = true,

true => this_sentence_is_false = false,

}

}

[dependent-distributive]

let be set of sets, let , and let be set of sets, index by its elements

union & intersection

draft of proof: 展开, 使用 distributive-forall-exists

sum & product

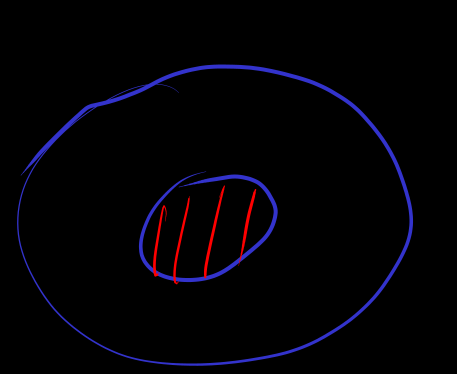

[set-minus]

. if then define

[symmetric-set-minus]